Frederick Wiseman Didn’t Just Film America—He Quietly Dissected It

Seeing one of Frederick Wiseman’s films for the first time has a certain eerie quality. You are not guided by the camera. Nothing is explained by it. It just sits there and watches, as though it has no purpose. But after a few minutes, it’s evident that something more profound is taking place. Slowly and uneasily, reality starts to emerge.

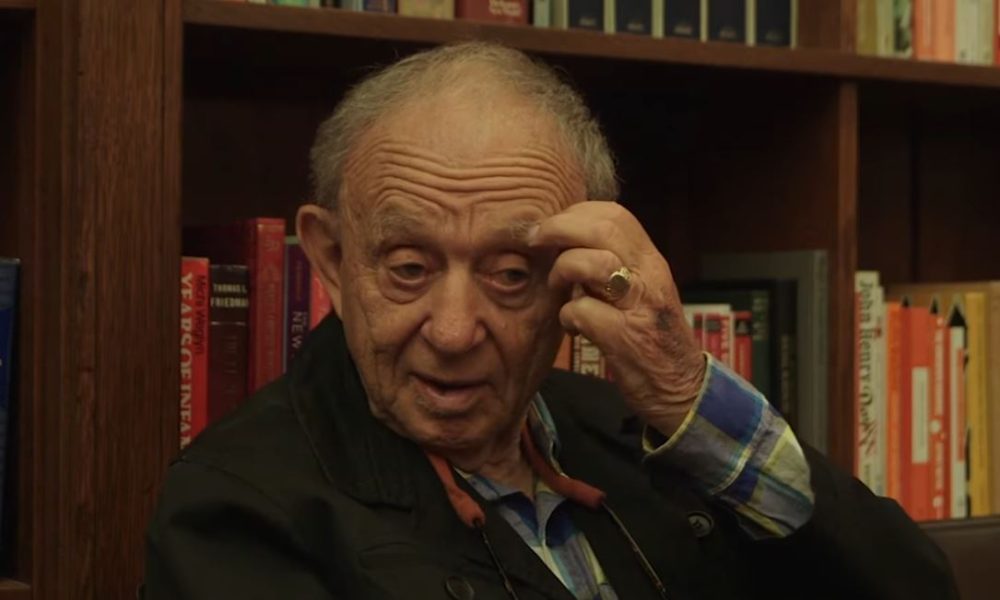

Wiseman spent almost 60 years filming American institutions, including schools, hospitals, welfare offices, and ballet companies, without commentary or narration, and without directing viewers’ thoughts. He passed away in February 2026 at the age of 96. It’s possible that his films were particularly unnerving because of this refusal to provide an explanation. He had greater faith in the audience than most filmmakers ever had.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Frederick Wiseman |

| Born | January 1, 1930, Boston, Massachusetts, USA |

| Died | February 16, 2026, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA |

| Profession | Documentary filmmaker, director, producer |

| Famous For | Observational documentaries on institutions |

| Breakthrough Film | Titicut Follies (1967) |

| Total Films | Over 45 documentaries |

| Awards | Honorary Academy Award (2016), Venice Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement |

| Style | Direct Cinema, no narration or interviews |

| Official Website | https://zipporahfilms.com |

Titicut Follies, his debut film, came about almost by chance. Wiseman visited Bridgewater State Hospital, a Massachusetts prison for the criminally insane, in the middle of the 1960s while teaching law. He witnessed prisoners being force-fed, humiliated, and ignored as he passed through its dim hallways. He remembered the scenes. His 1967 film so blatantly revealed those conditions that it was outlawed for over two decades. There is a sense of intrusion when viewing it now, even after several decades, as though something private was never intended to be seen.

Wiseman had no interest in being famous. He avoided theatrical gestures, spoke calmly, and wore simple clothing. However, his movies exuded subdued power. He filmed Philadelphia classrooms for his 1968 film High School, which showed teachers giving students lectures with a firmness that bordered on military. Students sat rigidly in rows as the fluorescent lights flickered above their heads. Narration was unnecessary. There was already tension.

It’s difficult to overlook his patience as a filmmaker. Wiseman frequently recorded hundreds of hours of video, which he then edited into films that occasionally lasted longer than three or four hours. Such length would never be permitted by most studios. He appeared unconcerned. It seems as though he thought truth took time.

His camera roamed around establishments like a silent guest.

He captured people waiting in claustrophobic government offices in Welfare (1975), their faces worn out and their voices rising in annoyance. Tension permeated the air as the chairs were arranged in stiff lines. Officials shuffled papers, providing assistance that frequently seemed inadequate. The movie never made its message clear. It didn’t have to.

“Documentary” was a word Wiseman detested. It sounded too clinical to him. He liked to think of his films as just movies, with stories developing organically. To him, that distinction was important. He wasn’t taking notes. He was watching behavior.

His subsequent motion pictures became even more expansive.

In his 2017 book Ex Libris: The New York Public Library, Wiseman documented quiet reading rooms, lectures, and meetings. There is a sense that democracy itself is being scrutinized as librarians discuss budgets and community initiatives. Whether or not viewers were aware of his films’ political content is still up for debate. He never spoke louder. He didn’t have to.

Even into his nineties, he never stopped working.

Menus-Plaisirs Les Troisgros (2023), his last movie, followed a French family as they operated a restaurant. The kitchens were bustling with activity. Dishes were expertly plated by chefs. Nothing noteworthy occurred. Nevertheless, everything did. Seeing people work, focus, pause—it was a completely different experience.

Quietly, Wiseman’s influence grew.

He was admired by filmmakers. He was admired by critics. However, his movies were never huge hits. They needed time. They were demanding attention. His silence felt almost rebellious in a time of rapid editing and incessant stimulation.

Wiseman seems to have grasped a fundamental aspect of human nature.

When people believe no one is judging them, they act differently. His camera was unbiased. It just observed.

He once claimed that prior to filming, he typically knew nothing about his subject. His work was influenced by that ambiguity. He had nothing to prove. He was finding one.

He spent the majority of his life in Cambridge, Massachusetts, editing movies in small spaces while the outside world became faster and louder. His method remained constant. He had faith in observation.

It feels different to watch his films now.

Organizations have evolved. Technology has evolved. But contrary to popular belief, human behavior hasn’t changed all that much. Authority continues to assert itself. Lines of people are still waiting. Most of us never see the rooms where decisions are still made.

Throughout his life, Frederick Wiseman exhibited those rooms.

It’s difficult to avoid wondering who else is still observing now that he’s gone.

Bitcoin

Bitcoin  Ethereum

Ethereum  Tether

Tether  XRP

XRP  USDC

USDC  Solana

Solana  TRON

TRON  Lido Staked Ether

Lido Staked Ether  Cardano

Cardano  Avalanche

Avalanche  Toncoin

Toncoin